Designing a mini Roomba

Perception, planning and controls for mobile robotics in 2D

This project is part of the course “Introduction to Robotics” taught by professor Henrik Christensen in the Computer Science Department at UC San Diego. Link of the course is here: http://www.hichristensen.net/CSE276A-23/index.html

Project repository: https://github.com/fjzs/mobile-robotics-2d

1 Problem Definition

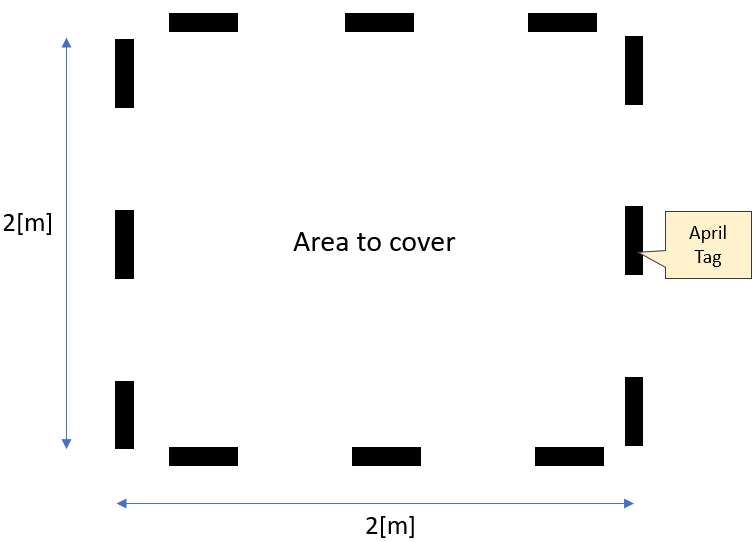

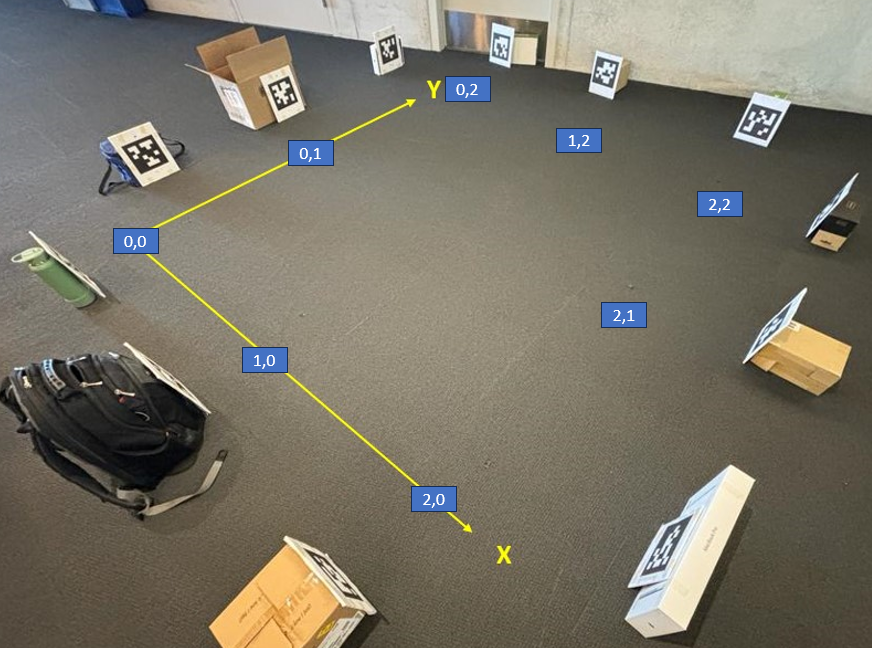

Given a Four Mecanum Wheeled Mobile Robot, design a “Roomba”-like system for a 2 x 2 square meters zone (free of obstacles). Use 12 April Tags to localize the robot as shown in Figure 1. Provide an algorithm to clean the zone, a video of it and a performance guarantee for this coverage.

1.1 What is a Four Mecanum Wheeled Mobile Robot?

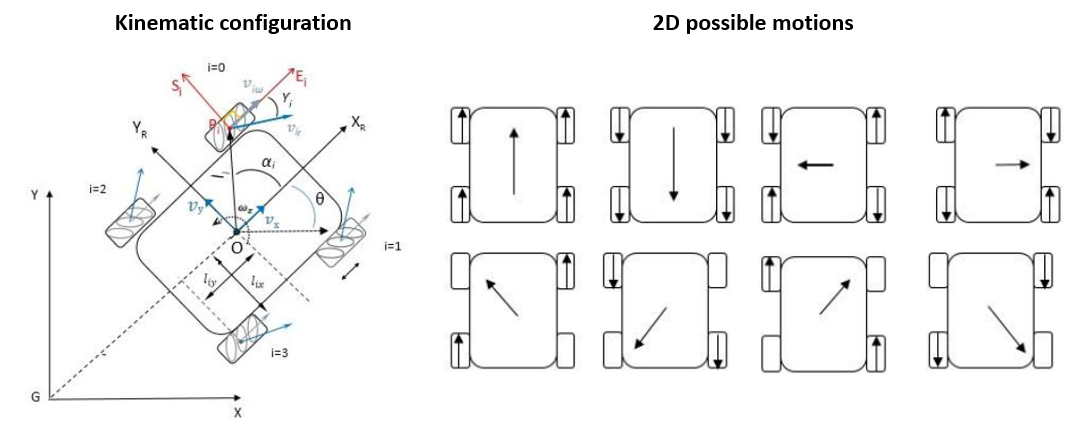

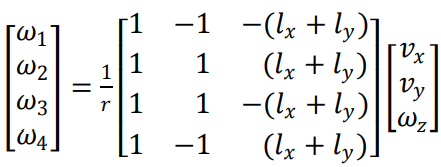

A mecanum wheel is an omnidirectional wheel design, providing the capability to move in 2D and rotate along the z axis, as opposed to traditional wheels that can only move in 1D. In this project we followed and implemented the kinematic model provided by Taheri et al (2015) (https://research.ijcaonline.org/volume113/number3/pxc3901586.pdf). In Figure 2 you can see the kinematic configuration of this robot. Each wheel \(i\) has an angular velocity of \(\omega_i\), providing the robot with a 2D velocity \((v_x, v_y)\) and a rotation around the z axis (yaw) given by \(\omega_z\).

1.2 The particular robot used

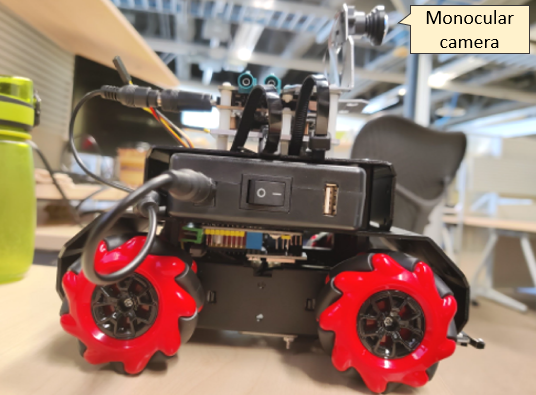

In this project the robot consisted in a Mbot Mega (4 mecanum wheel robot) + Qualcomm RB5 board. This robot is equipped with a monocular camera that we will use for perceptions tasks. You can see it in Figure 3.

1.3 What is an April Tag and how to use it for localization

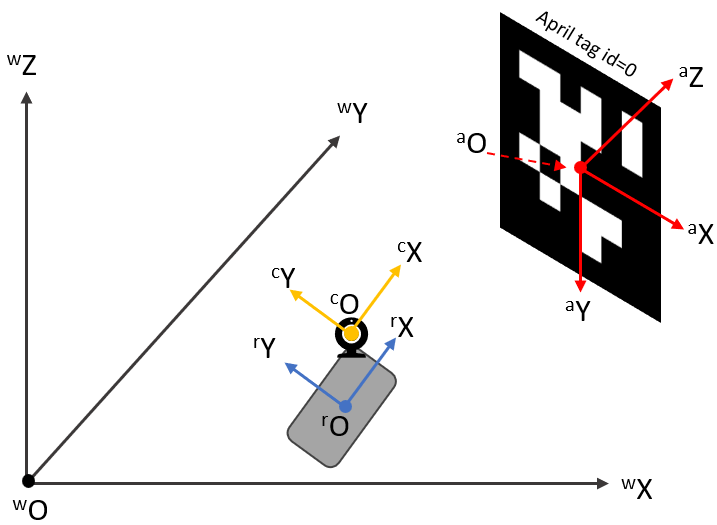

April Tag is a visual system developed at University of Michigan (https://april.eecs.umich.edu/software/apriltag). It’s like a QR code that can be read by a library developed by the authors. In Figure 4 there is a description of how this works. Given the coordinate frames of the world (w), robot (r), robot’s camera (c) and april tag (a), when the robot’s camera reads an april tag, the library retrieves both the id of the tag and the 4x4 transformation \(^{c}T_{a}\), which is the relative transformation that takes a point in the april tag coordinate frame to the robot’s camera coordinate frame. Then, using that \(^{c}T_{a} = (^{a}T_{c})^{-1}\), we can get the robot position (x,y,z) and orientation (roll, pitch, yaw) in the world frame using the following equation:

\[^{w}T_{r} = ^{w}T_{a} \cdot ^{a}T_{c} \cdot ^{c}T_{r}\]

2 Solution

We used ROS + python as the main framework to develop this project. The environment of this project is shown in Figure 5.

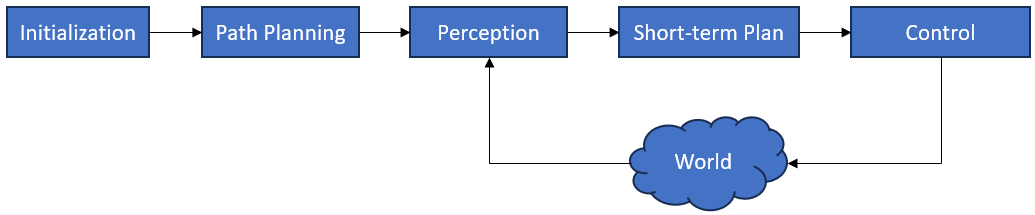

The architecture of our system is shown in Figure 6. In the next subsections we explain the responsibilities of each module.

2.1 Initialization

This module is responsible for configuring the environment and the robot in the system, such as:

- The size of the environment

- The coordinate frame of the world frame

- The transformations matrices (orientation and position) of each april tag in world frame

- The initial position of the robot

- The transformations matrices of the robot’s camera with respect to the robot

- The time interval of the loop (for instance, 0.05 seconds)

- The parameters of the kinematic model of the robot

2.2 Path Planning

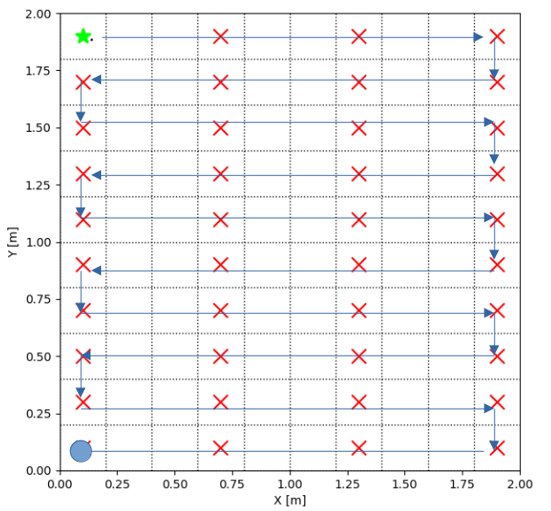

This module is responsible for providing a set of waypoints \((x, y, \theta)\) for the robot to follow in order to cover the area. To do this, first a world representation is created, which in this case corresponds to a 2D grid. The size of each cell is a parameter of the module. In this project we chose to use 0.2 [m] as the cell side length, because the robot length is roughly 0.2 [m] as well. Then, given this grid, another algorithm decides how to cover it. In this case we chose a mine sweeper style to cover the grid (graph), which is shown in Figure 7.

2.3 Perception

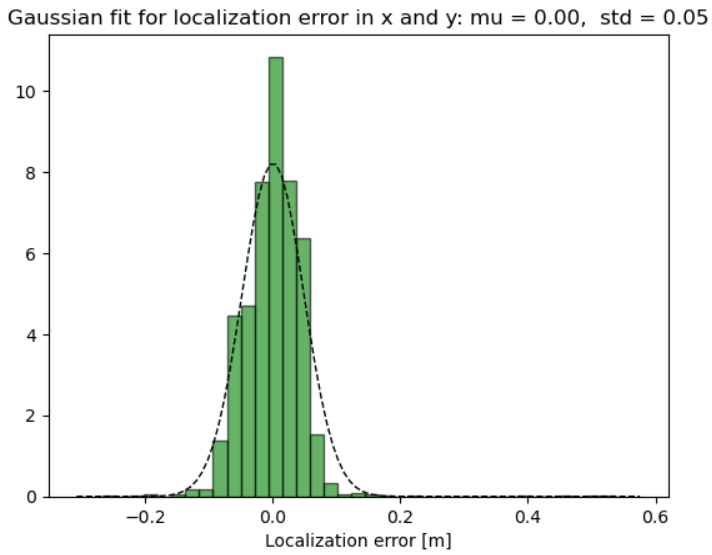

The only sensor of this robot is the camera, which is used to detect April Tags. Then, as shown in section 1.3, we can use the April Tag library to estimate the robot state given by its position and orientation \((x,y,\theta)\). In this environment, nonetheless, the robot is going to detect multiple April Tags, all of them in different ranges and with different magnitudes of noise (given by illumination, motion, blurriness, etc). To handle the noise and to provide the best estimation of the robot state we used the median of the April Tag detections, which reduced the noise, but to a point where it was manageable. We also measured the noise of this approach by sampling the localization error on different robot positions, and found out that the localization error distributes ~ \(N(0, 0.05)\) as shown in Figure 8.

2.4 Short-term Plan

This module is responsible for deciding at every time step \(t\) the velocity of the robot \((v_x, v_y, \omega_z)\) given the current robot state \(s_t\) and the next waypoint \(w\) to reach. To get this velocity we used a PID controller, with minimum and maximum values for the norm of the velocity vector.

Then, given this velocity \((v_x, v_y, \omega_z)\), this module also translates this into angular velocities \(\omega_i\) for each wheel \(i\) given the kinematic model of the robot. Figure 9 shows the kinematic model of this type of robot.

2.5 Control

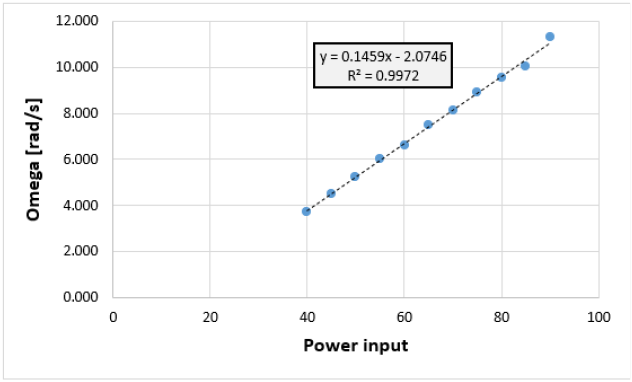

This module is responsible for translating the angular velocities \((\omega_1, \omega_2, \omega_3, \omega_4)\) required by the Short-term Planning module into motor commands to achieve those velocities. Sometimes this task is also called “calibration”. To do this, I sampled multiple straight trajectories of the robot given different motor commands (which I refer to “power”, they could be anywhere from -5000 to 5000). With this experiment I could get a function relating power to the wheel to angular velocity of the wheel, as shown in Figure 10.

3 Results

3.1 Robot trajectory

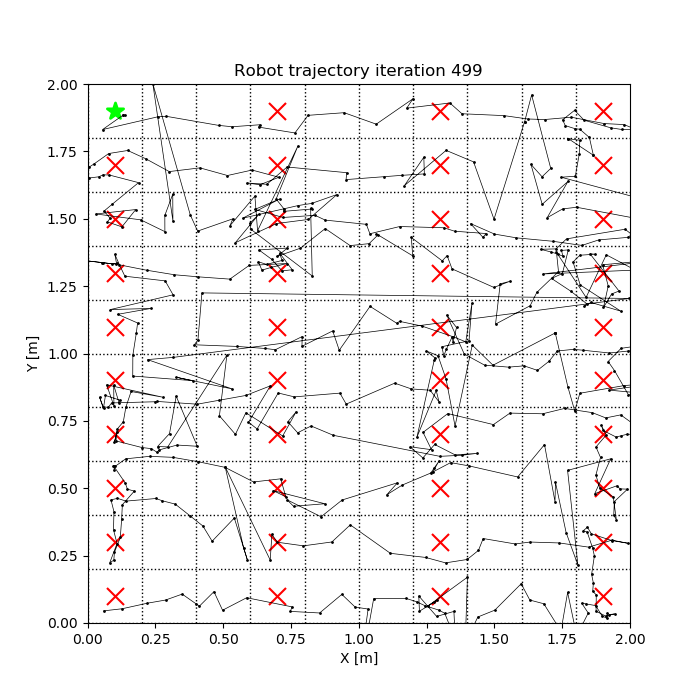

In Figure 11 we show the trajectory estimated by the robot perception stack throught its journey. The video associated to this experiment can be seen in this link: https://youtu.be/yTnWUw7eKxI.

3.2 Performance guarantee

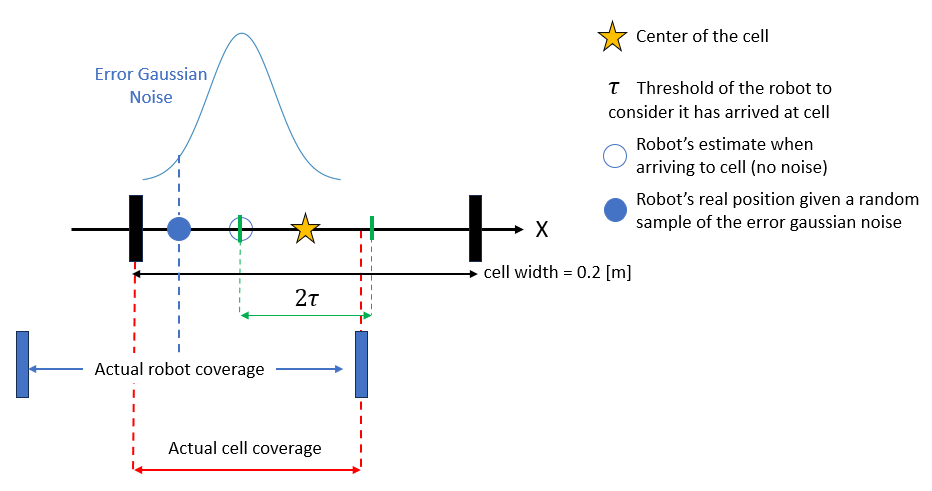

In this section we explain a simplified approach to provide a performance guarantee considering only a single dimension. The question we are trying to answer here is: what is the expected coverage percentage of our robot in a 1D grid cell, considering that the localization error follows a probability distribution and that the robot is considered to cover that cell when it is at a minimum threshold distance? Figure 12 shows our method.

By using Monte Carlo simulation on this stochastic system we can expect on average, that each cell of the grid is going to be covered roughly by 47% on the first pass of the roomba.